Over the past few years the space of generative AI (formerly generative models) has been dominated by diffusion models due to their unconstrained neural network architecture, simulation based sample generation and fast, simulation-free training. At the core of diffusion models is a neural network that serves as a parametric approximation of the score function, which is then used to construct an SDE whose solution yields samples. However, there is a different class of generative models, called continuous normalizing flows (CNF), that have many of same benefits of diffusion models, but are based on parametrizing the ODE whose solution yields samples. In this post, we'll go over a brief history of CNFs, how they are constructed, their existence and end with some training algorithms.

Brief history

Continuous normalizing flows were first introduced in the 2018 Neural ODE paper. The authors introduced the instantaneous change of variables formula, which opened the possibility to train CNFs via maximum likelihood. In the following years, there was three main branches of research on CNFs.

1) Improved training and sampling speed (Grathwohl et al. 2019, Finlay et al. 2020, Kidger et al. 2021 to name a few)

2) Extensions to Riemannian manifolds (Mathieu and Nickel 2020, Falorsi 2021, Lou et al. 2020). However, CNFs were too difficult to train in practice which stopped them from receiving as much attention as other flow based methods for generative modeling.

3) Alternatives to maximum likelihood for training (Rozen et al. 2021, Ben-Hamu et al. 2022, Liu et al. 2022, Lipman et al. 2023, Albergo and Vanden-Eijnden 2023)

The latter led to breakthroughs in training CNFs that make them competitive with diffusion models in image generation and generative modeling on manifolds.

What problem are we trying to solve?

We are interested in learning a parametric approximation of an unknown probability distribution that we can sample from and compute likelihood on. Given a target probability distribution called \(p_\text{data}(x)\), where \(x\in \mathcal{M}\), we want to learn a parametric approximation called \(p_\text{model}(x;\theta)\). In our problem setup, we assume that we can sample from \(p_\text{data}(x)\) and that \(p_\text{data}(x)>0, \forall x\in \mathcal{M}\). The second assumption ensures that a solution exists, as we will see later.

We have 2 goals: 1. Sample from \(p_\text{model}(x;\theta)\). 2. Compute the probability of a given sample \(x\) under \(p_\text{model}(x)\).

How do we solve this problem?

We will learn an invertible function, \(f: \mathcal{M} \to \mathcal{M}\) that is parametrized by \(\theta\), and specify a prior probability distribution over \(\mathcal{M}\) called \(p_0\) such that the following model produces a sample \(x\sim p_\text{model}(x;\theta)\):

We can compute the log likelihood of a sample \(x\) under \(p_\text{model}(x;\theta)\) by applying the change of variables formula:

The class of models that we just described is called normalizing flows. Continuous normalizing flows are a special kind of normalizing flow where \(f\) is constructed as the solution to an ODE.

Continuous normalizing flows

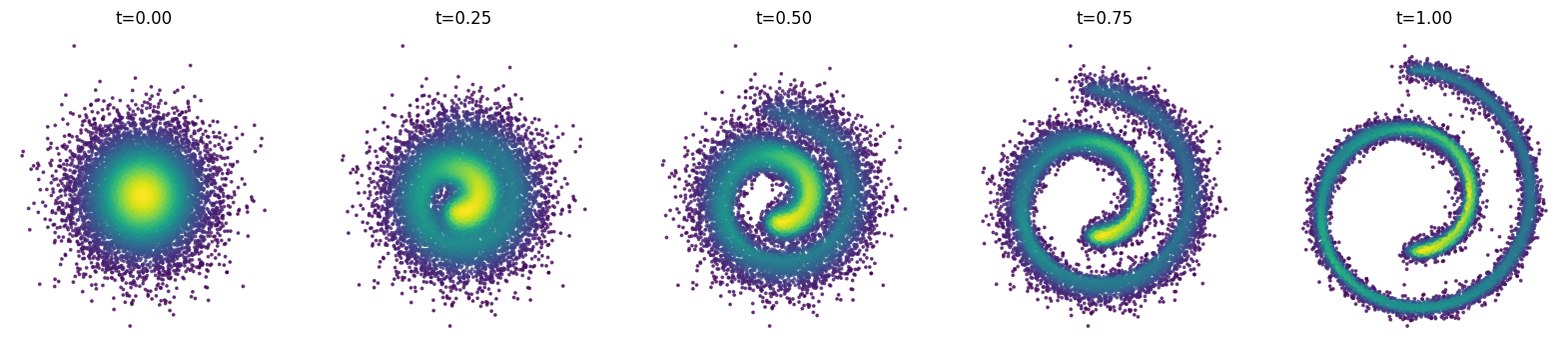

Continuous normalizing flows are a type of normalizing flow where \(f\) is a continuous function of \(t\in [0,1]\) and \(f_1\) is used in the computation of \(p_\text{model}(x;\theta)\). In this setting, we do not parametrize \(f_t: \mathcal{M} \to \mathcal{M}\) directly, but we instead parametrize its time derivative:

So we can generate samples from \(p_\text{model}(x;\theta)\) by first sampling \(x_0\sim p_0(x_0)\) and then integrating \(V_t(x_t;\theta)\) from \(t=0\) to \(t=1\). In order to get the log likelihood of a sample \(x\), we can compute the determinant of the Jacobian of \(f_1\) which is feasible with modern auto-diff packages like Diffrax or Torchdiffeq. However another alternative is to find how probability density function evolves over time and then integrating those dynamics.

Log likelihood dynamics

We are interested in finding how the probability density function, \(p_t\) will change when we move its samples along the vector field \(V_t\). In order to figure this out, we will need to figure out how \(p_t\) and \(V_t\) are related. The fundamental relationship that we will begin with is that probability mass is conserved as we flow on \(V_t\). This observation will lead us to the continuity equation which defines the dynamics of \(p_t\).

Continuity equation

Let \((\mathcal{M},g)\) be a Riemannian manifold with volume form \(\omega_g\), let \(V_t \in \mathfrak{X}(\mathcal{M})\) be a time dependent vector field on \(\mathcal{M}\) with flow \(f_t: \mathcal{M} \to \mathcal{M}\).

Say that at time \(t=0\) we want to compute the probability mass inside a region \(D \subseteq \mathcal{M}\). We can do this using our prior \(p_0\) by integrating over the region:

Similarly, at time \(t\) we can compute what the mass is of the same region after it has been flowed by \(V_t\):

where \(p_t\) is the pushforward measure of \(p_0\) under \(f_t\). The fundamental assumption that we can make is that \(P(x_0\in D) = P(x_t\in f_t(D))\). Intuitively this assumption makes sense because if we think about samples from probability distribution as "particles" distributed in space, then the flow cannot change the number of particles. With this in mind, we assert that the probability mass in \(f_t(D)\) does not change with respect to time:

The integrand of the last equation relates \(p_t\) and \(V_t\) and is called the continuity equation:

Instantaneous change of variables formula

In practice we are interested in computing the log likelihood of a sample \(x\) under \(p_\text{model}(x;\theta)\), which requires knowing how the log likelihood of a sample changes over time. This is the same as knowing how the log likelihood changes under the flow of \(V_t\) and time. In particular, we want to know \(\frac{d\log p_t(t,x(t))}{dt}\). In geometry terms, this is the same as knowing how \(\log p_t\) changes on the flow of \(\frac{d}{dt} + V_t\). Here, we assume that \((\frac{d}{dt}, \frac{d}{dx^1}, \dots, \frac{d}{dx^n})\) forms a basis for the space \(\mathbb{R} \times \mathcal{M}\), so the vector field \(\frac{d}{dt} + V_t = \frac{d}{dt} + V_t^i \frac{d}{dx^i}\) describes the flow of both time and points on the manifold.

Lets compute the Lie derivative of \(p_t\) with respect to \(\frac{d}{dt} + V_t\):

Dividing both sides by \(p_t\) gives us the final result:

Existence of CNFs

A natural question to ask is when a continuous normalizing flow even exists. Is it always possible to find a vector field whose flow pushes forward a user specified prior to any target probability distribution? The answer turns out to be yes as long as the prior and target are non degenerate everywhere on the manifold. The proof for this is called Moser's Theorem and it actually constructs the vector field that we need.

Let \((\mathcal{M},g)\) be a boundryless n-dimensional Riemannian manifold with volume form \(\omega_g\) and let \(p_t\) be a time dependent probability density so that \(\int_{\mathcal{M}}p_t\omega_g = 1\). We start the same way as we did in the continuity equation by asserting that the probability mass in \(f_t(D)\) does not change with respect to time so that \(\frac{d}{dt}\int_{f_t(D)}p_t\omega_g = 0\) for our flow \(f_t\). However, we don't know what vector field generates \(f_t\). We will proceed by assuming that there is a solution called \(V_t\) and then we'll show what \(V_t\) must be equal to. Using the steps from deriving the continuity equation, we have

The trick to Moser's theorem is that we can actually show that \(\frac{d p_t}{dt}\omega_g\) is a closed form, meaning that there exists some \(n-1\) form, \(\beta_t \in \Omega^{n-1}(\mathcal{M})\), so that \(d\beta_t = \frac{d p_t}{dt}\omega_g\) where \(d\) is the exterior derivative. As we will show, this is true because \(p_t\) integrates to 1.

The Hodge decomposition tells us that any top form can be decomposed into a sum of a closed form \(d\beta_t\) and a harmonic form \(\gamma_t\), so \(\frac{d p_t}{dt}\omega_g = d\beta_t + \gamma_t\). Because we are dealing with top forms, we know that \(\gamma_t\) is a scalar multiple of the volume form, \(\gamma_t = c\omega_g\). We can solve for what \(c\) is by exploiting the fact that \(p_t\) integrates to 1:

Therefore \(c=0\) and we have that \(\frac{d p_t}{dt}\omega_g = d\beta_t\). Plugging this into our equation from before, we have

So now the question that we need to answer is: Does there exist a vector field \(V_t\) so that \(V_t \lrcorner p_t \omega_g + \beta_t = 0\) where \(\beta_t \in \Omega^{n-1}(\mathcal{M})\)? The answer is yes! The reason is that we can always write an \(n-1\) for as the interior product with the volume form, so there exists a vector field \(U_t\) so that \(\beta_t = U_t \lrcorner \omega_g\). Therefore, we can simplify more:

We know that the integrand has to be \(0\), so we can solve for \(V_t\) in terms of \(p_t\) and \(U_t\):

And we're done! We have constructed our time dependent vector field whose flow generates the probability path \(p_t\) for all \(t\).

How to train CNFs

There are 2 main ways to train CNFs: 1. Maximum likelihood estimation 2. Score/flow matching

Maximum likelihood estimation

MLE is the simplest way to train CNFs. Since we can compute the log likelihood of a sample \(x\) under \(p_\text{model}(x;\theta)\), we can just use gradient descent to maximize the log likelihood of the training data. The only tricky part is that if our data is high dimensional, then the \(\text{Tr}(\nabla_x V_t)\) term in the instantaneous change of variables formula will be expensive difficult to compute because we will need to explicitly compute the Jacobian matrix of \(V_t\). However, we can use Hutchinson's trace estimator to get an unbiased estimate which is good enough in practice:

We can compute \(\nabla_x V_t\epsilon\) almost as efficiently as computing \(V_t\) using autodiff using a JVP or VJP. The advantage to using this method is that we can optimize different kinds of objectives like the reverse KL divergence or the forward KL divergence. The disadvantage is that we need to simulate the dynamics of the model at each time step to get a good approximation of the log likelihood. Furthermore, if the target distribution is 0 in some places, which is happens if the dataset lies on a manifold, then \(\log p_\text{model}(x;\theta)\) will be trained to approach infinity. An alternative that avoids this problem is to use matching.

Flow matching

In the setting where we have samples from our target density, you should always use flow matching to train your model. See my post on flow matching for more details.